Watrous is located at the place where the Mountain Branch and the Cimarron Cutoff of the Santa Fe Trail came together. The Mora and Sapello Rivers meet just east of town and made this an excellent watering hole. Lots of cottonwoods, great grass, protected areas from the weather, all combined to make Watrous a good stopping and resting point. When the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad finally came through in 1880-81, Watrous became the major stop for materials headed for Fort Union, just a few miles north of town on the Mountain Branch of the Santa Fe Trail. In the days of the steam locomotives, this was probably a place where the engine took on water.

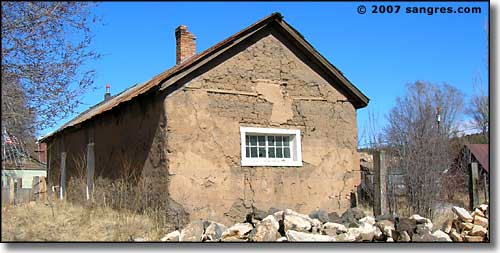

Today, there's almost no local retail business but yesterday, well, a short drive through town will show you that there was once a pretty good commercial climate here, especially for supplying the large cattle and horse ranches around the area.

Watrous is about 16 miles northeast of Las Vegas, just over the county line in Mora County. 170 years ago, Mora County was one of the centers of European settlement in New Mexico but today, it's one of the least prosperous counties in all of America.

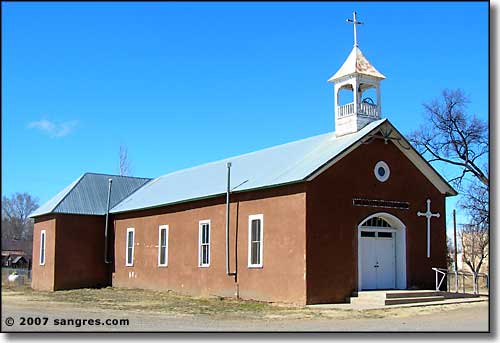

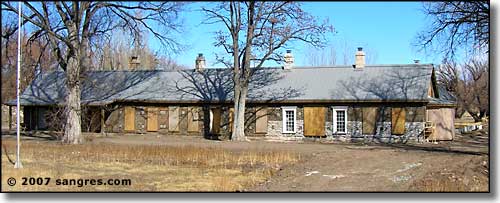

When I drive into a town like this to take photos, I'm looking for the historic stuff and anything modern that really sticks out. Watrous does have newer homes in town but I shot what I thought was "remarkable."

Update: 2007. I found some new data regarding the founding of what is now Watrous:

In March of 1848, Alexander Barclay and George Simpson travelled down the Mora River to its' junction with the Sapello at a small settlement called La Junta (which is now known as Watrous). This was the Scolly Grant and had been occupied by a poor farmer named James Bonney (he was the person who built the houses at the river junction). Thomas Fitzpatrick had previously told Barclay and Joseph Doyle (who were business partners at the time) that the US Government would probably build a fort in the area to protect travellers on the Santa Fe Trail from marauding Indians. The plan was to build a fort here and then sell it to the government for a profit. This was also a great location to establish a mercantile for trading with travellers on the Trail because it was just south of the point where the Cimarron Cutoff and the Mountain Branch merged. Barclay quickly went to Santa Fe and bought the Scolly Grant.

On April 23, 1848, the largest caravan ever to cross Raton Pass left Pueblo and headed south, intent on reaching the Scolly Grant and establishing a settlement there. After leaving the women and children in Mora, the men arrived at the Grant and began the work (just west of where the I-25 passes through now). Soon after, Charles Autobees came from Mora to supervise the construction of the adobe Fort Barclay. Shortly, two irrigation ditches had been dug to water the 200 acres that were already under cultivation.

By September 4, the fort was sufficiently complete that Barclay brought his wife, Teresita Suaso, to her new home. On September 19, Doyle arrived with a blacksmith. A few days later, Doyle brought his own wife down from Mora. A mercantile was set up and did a reasonably prosperous business (but, of course, business was never as good as they had dreamed it would be). Soon there was also a post office established and Fort Barclay served a pretty large chunk of New Mexico countryside.

In 1850, Barclay tried to sell the fort to the Army but they wouldn't buy it. Instead, a Colonel Sumner tried to order Barclay off his own land so the Army could build their own fort there. Then in 1851, Fort Union was built on a parcel of land near Barclay's property. Again the Army tried to order him off his own land but he took it to court and won. The court ordered the Army to pay Barclay $1,200 per year to rent the land they'd built on.

In 1853, Barclay made a trip north to trade with the Indians and found they'd moved from where he thought they were. He suffered a large financial loss. When he returned to the fort he found that things had gotten pretty crazy there and, by the end of October, he was living at the fort by himself. He advertised the fort for sale in the Santa Fe newspapers but never had an inquiry. He got very ill and finally died and was buried at the fort in December, 1855.

Litigation over the property had gone on for several years but, in the end, Joseph Doyle retained title to the Scolly Grant and finally sold it to William Kronig and Morris Beilschowski in 1856 for about $7,000.

In September of 1848, Samuel B. Watrous had sent some men to property he owned to the east of the Scolly Grant and just north of the junction of the Mora and Sapello Rivers. They began construction of a home and trading post for his business. Watrous arrived in March, 1849, and settled in. His business was either better than Barclay's or he wasn't as ambitious because he stayed in the area for the rest of his life. He also did a lot of farming and was highly respected for his efforts. In 1879, the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe was coming near. He knew what that was worth so he donated a pretty good chunk of land for them to build a trackyard and station just south of his home. When construction on the station was finished, he went to the grand opening and saw his name "Watrous" spelled out on the side of the building. The townsite was surveyed and registered by the railroad and has been called Watrous ever since.

Another funny item: years after Fort Union was abandoned it was determined that the Mora Grant predated the Scolly Grant in terms of ownership of the land where Fort Union was built. Whatever lease money the Army paid to Barclay and Doyle should actually have been paid to the owners of the Mora Grant, but it looks like Barclay and Doyle were better connected politically (especially among the territorial judiciary) and that's really what counted in those days.