|

Santa Fe National Historic Trail |

The Santa Fe Plaza in early Trail days |

The Great Prairie Highway

The Santa Fe Trail stirs imaginations as few other historic trails can. For 60 years, the Trail was one thread in a web of international trade routes. It influenced economies as far away as New York and London. Spanning 900 miles of the Great Plains between the United States (Missouri) and Mexico (Santa Fe), it brought together a cultural mosaic of individuals who cooperated and sometimes clashed. In the process, the rich and varied cultures of Great Plains Indian peoples caught in the middle were changed forever. Soldiers used the trail during the 1846-1848 Mexican-American War, 1840s border disputes between the Republic of Texas and Mexico, and America's Civil War. The troops also policed conflicts between traders and Indian tribes. With the traders and military freighters tramped a curious company of gold seekers, emigrants, adventurers, mountain men, hunters, American Indians, guides, packers, translators, invalids, reporters, and Mexican children bound for schools in Los Estados Unidos. Spain jealously protected the borders of its New Mexico colony, prohibiting manufacturing and international trade. Missourians and others visiting Santa Fe told of an isolated provincial capital starved for manufactured goods and supplies - a potential gateway to Mexico's interior markets. In 1821, the Mexican people revolted against Spanish rule. With independence, they unlocked the gates of trade, using the Santa Fe Trail as the key. Encouraged by Mexican officials, the Santa Fe trade boomed, strengthening and linking the economies of Missouri and Mexico's northern provinces. The close of the Civil War in 1865 released America's industrial energies, and the railroad pushed westward, gradually shortening and then replacing the Santa Fe Trail. In 1821 the eastern terminus was Franklin, Missouri; by 1832, Independence, Missouri; and by 1845, Kansas City, Missouri. Textiles and hardware were traded west, silver, mules and furs were traded east. Life on the Trail

Movies and books often romanticize Santa Fe Trail treks as sagas of constant peril, replete with violent prairie storms, fights with Indians, and thundering bison herds. In fact, a glimpse of buffalo, elk, pronghorns, or prairie dogs was sometimes the only break in the tedium of the 8 week journey. Trail travelers mostly experienced dust, mud, gnats, mosquitos, and heat. But, occasional swollen streams, wildfires, hailstorms, strong winds, or blizzards could imperil wagon trains. At dawn, trail hands scrambled in noise and confusion to round up, sort and hitch up the animals. The wagons headed out, the air ringing with cries of "All's set!" and soon, "Catch up, catch up!" and "Stretch out!" Stopping at mid-morning, crews unhitched and grazed the teams, hauled water, gathered wood or buffalo chips for fuel, and cooked and ate the day's main meal, from a monotonous daily ration of 1 lb. of flour, 1 lb. or so of sowbelly bacon, 1 oz. of coffee, 2 oz. of sugar, and a pinch of salt. Beans, dried apples, or buffalo and other game were occasional treats. Crews then repaired their wagons, yokes and harnesses; greased wagon wheels; doctored animals; and hunted. They moved on soon after noon, fording streams before that night's stop because overnight storms could turn trickling creeks into raging torrents before morning. And stock that was cold in the harness first thing in the morning tended to be unruly. At day's end, crews took care of the animals, made necessary repairs, chose night guards, and enjoyed a few hours of well-earned leisure and sleep. |

"The Vast Plain, Like a Green Ocean"

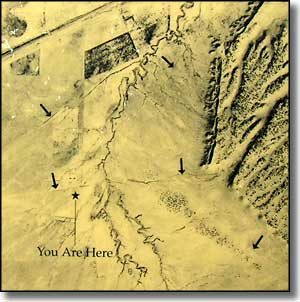

Westward from Missouri, forests - and then tall-grass prairie - give way to shortgrass prairie in Kansas. In western Kansas, roughly at the Hundredth Meridian, semi-arid conditions develop. For Trail travelers, venturing into the unknown void of the Plains could hold the fear of hardship or the promise of adventure. Long days travelling through seemingly endless expanses of tall- and shortgrass prairie, with a few narrow ribbons of trees along waterways, evoked vivid descriptions. "In spring, the vast plain heaves and rolls around like a green ocean," wrote one early traveler. Another marveled at the mirage in which "horses and the riders upon them presented a remarkable picture, apparently extending into the air ... 45 to 60 feet high ... At the same time I could see beautiful clear lakes of water with ... bullrushes and other vegetation..." Other Trail travelers dreamed of cures for sickness from the "purity" of the plains. (The photo to the right is from a 1930's aerial shot showing existing wagon ruts in the area around Iron Spring) Deceptively empty of human presence as the prairie landscape might appear, the lands the Trail passed through were the long-held homelands of many American Indian peoples. Here were the hunting grounds of the Comanches, Kiowas, southern bands of Cheyennes and Arapahos, and Plains Apaches as well as the homelands of the Osages, Kansas, Jicarilla Apaches, Utes, and Pueblos. Most early encounters were peaceful negotiations centering on access to tribal lands and trade in horses, mules, and other items that Indians, Mexicans and Americans coveted. As Trail traffic increased, so did confrontations - resulting from misunderstanding and conflicting values - that disrupted traditional American Indian lifeways and Trail traffic. Mexican and American troops provided escorts for wagon trains. Growing numbers of Trail travellers and settlers moved west, bringing the railroad with them. As lands were parceled out and the bison were hunted nearly to extinction, Indian peoples were pushed aside or assigned to reservations. |

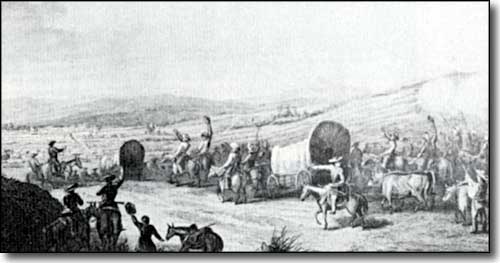

Caravan arriving from Missouri, from Josiah Gregg's Commerce of the Prairies |

|

Soldiers and Forts

Suspicion and tension between the United States and Mexico accelerated in the 1840s, because Americans wanted territorial expansion. Texans raided into New Mexico, and the United States annexed Texas. The Mexican-American War erupted in 1846. General Stephen Watts Kearny led his Army of the West down the Santa Fe Trail, to take and hold New Mexico and Upper California and to protect American traders on the Trail. He marched unchallenged into Santa Fe, and, although communities such as Taos and Mora staged revolts, American control prevailed. In 1848 the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ended the war. The Santa Fe Trail became the lifeline for protection and communication between Missouri and Santa Fe. From a succession of military forts such as Mann (1847), Atkinson (1850), Union (1851), Larned (1859), and Lyon (1860), the Army controlled conflicts between American Indians and Trail travelers. As the military presence grew, freighting and merchant operations burgeoned. In 1858, many of the 1800 wagons traveling the Santa Fe Trail carried military supplies. In 1862, the Civil War arrived in the West. Confederates from Texas pushed up the Rio Grande Valley into New Mexico, intent on seizing the territory and Fort Union, and ultimately, the rich Colorado gold fields. Albuquerque and Santa Fe fell. But the tide turned at Glorieta Pass, New Mexico, on the Santa Fe Trail in the most decisive western battle of the Civil War. Union forces secured victory when they torched the nearby Confederate supply train. The Confederates abandoned hope of reaching Fort Union - and of keeping their foothold in New Mexico. The Union Army held the Southwest and its vital Santa Fe Trail supply line. |

The view near Iron Spring |

Commerce of the Prairies

The story of the Santa Fe Trail is a story of business - international, national and local. In 1821, William Becknell, bankrupt and facing jail for debts, packed goods from Missouri to Santa Fe and made a profit (some say he was waiting at the Arkansas River, near where Bent's Old Fort would be, for word to come that Mexico had declared independence from Spain and that he would be safe to cross the river into Mexican territory). Entrepreneurs and other experienced business people followed - James Webb, Antonio José Chavez, Charles Beaubien (of the Beaubien-Miranda and Sangre de Cristo Land Grants), David Waldo, and others. The Santa Fe trade developed into a complex web of international business, social ties, tariffs, and laws. Merchants in Missouri and New Mexico extended connections to New York, London and Paris. Traders exploited legal and social systems to facilitate business. Partnerships such as Goldstein, Bean, Peacock & Armijo formed and dissolved. David Waldo "converted" to Catholicism - and also became a Mexican citizen. Dr. Eugene Leitensdorfer, of Missouri, married Soledad Abreu, daughter of a former New Mexico governor. Trader Manuel Alvarez claimed citizenship in Spain, the United States and Mexico. After the Mexican-American War, Trail trade and military freighting boomed. Both firms and individuals obtained and subcontracted lucrative government contracts. Others operated mail and stagecoach services. |

A Santa Fe Trail marker near Iron Spring, southwest of Timpas, Colorado |

|

Maps of the Santa Fe Trail Selecting one of these buttons will bring you a large version of the map you request. To return, use the Back button of your browser. Colorado-New Mexico section of Trail Complete Trail, large image, 564K |

|

| Index - Arizona - Colorado - Idaho - Montana - Nevada - New Mexico - Utah - Wyoming National Forests - National Parks - Scenic Byways - Ski & Snowboard Areas - BLM Sites Wilderness Areas - National Wildlife Refuges - National Trails - Rural Life Advertise With Us - About This Site - Privacy Policy |

|

I think the painting at the top of this page is from the Museum of New Mexico. Color photos courtesy of Sangres.com, CCA ShareAlike 3.0 License. Text Copyright © by Sangres.com. All rights reserved. |