Pecos National Historical Park

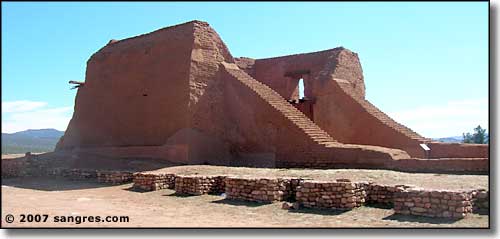

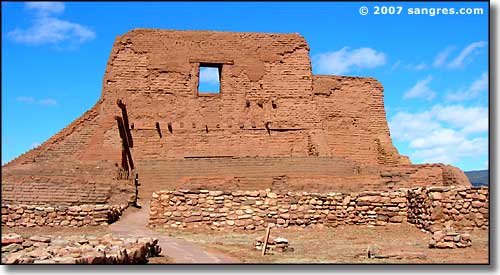

Ruins of the second Pecos Mission Church

Located at the midpoint in a natural passage through the southern Sangre de Cristo Mountains, Pecos Pueblo was a economic power, dominating trade between the Rio Grande Pueblos and the Plains Indians to the east. Describing the pueblo in 1584, a Spanish conquistador wrote that it was on a "high and narrow hill, enclosed on both sides by two streams and many trees. The hill itself is cleared of trees... It has the greatest and best buildings of these provinces and is most thickly settled... They possess quantities of maize, cotton, beans, and squash. [The pueblo] is enclosed and protected by a wall and large houses, and by tiers of walkways which look out on the countryside. On these they keep their offensive and defensive arms: bows, arrows, shields, spears, and war clubs." The Pecos people had obviously learned that the Plains Indians they sometimes traded with could be very unpredictable at times. The neighboring pueblos viewed Pecos as a dominant political, economic and military force in their world. The Spaniards soon learned that Pecos could be a powerful ally, or a determined enemy.

About 800 CE, the first inhabitants in the area were hunter-gatherers who lived in pithouses along the drainages. It was around 1100 that the first rock-and-mud villages began to appear. About two dozen of these villages were built in the vicinity before things changed radically in the 1300's. Within one generation, most of the outlying villages were abandoned with everyone moving into the defensible position where Pecos Pueblo stands. The time period is concurrent with the arrival in the area of nomadic and marauding Plains Indians. By 1450, Pecos (or as it was then known "Cicuyé") had grown into a 5-story, well planned frontier fortress housing 2,000 people.

The Pecos were excellent farmers, growing abundant crops in the topsoils collected by check dams they built in the drainages to slow the rain and snow runoff. When Francisco Vasquez de Coronado came through with his men in 1541, he estimated that the pueblo's storerooms held a three-year supply of corn alone.

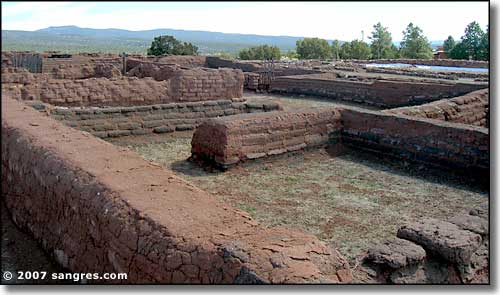

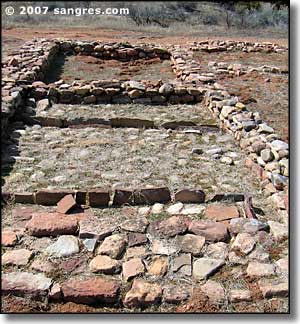

These ruins are outside the main pueblo construction and were discovered underneath the pueblo's huge trash pile

These are the remains of the rock-and-mud village that was here before the pueblo itself was built

In 1536, Cabeza de Vaca stumbled his way back into Mexico after being shipwrecked and wandering all over New Spain's northern frontier. He told stories of tantalizing legends and rich cities further north: the famous "Seven Cities of Cibola." In 1540, Francisco Vasquez de Coronado led an army of 1,200 men (and a gang of Franciscan missionaries) northward out of Mexico in search of the legendary treasures. Six months into the journey, he found Cibola (a cluster of Zuni pueblos near present-day Gallup). The Zuni weren't particularly welcoming so Coronado attacked them and took over Háwikuh, their principal town. Then he raided their food stores for his famished soldiers.

150 miles east of there, he came across Cicuyé. The reception here was much more to his liking and he and his men camped out for a while. While they were here, the gray-clad Franciscans went around planting crosses for their strange god and preaching their abomination of a religion (remember: these monks were emissaries of the Spanish Inquest which was still in the depths of depravity in Europe). Then the elders of the Pueblo introduced Coronado to a captive Plains Indian. This captive told him stories of Quivira, a rich land far to the east. In the spring of 1541, Coronado and his men left Cicuyé with this Plains Indian as a guide and headed east. After wandering far into Kansas and finding only a few poor villages, the guide confessed that he'd led Coronado onto the Plains to die. Coronado had him strangled and then headed back west. His weakened and broken army spent a bleak winter on the Rio Grande before making their way back to Mexico empty-handed. They were harassed by Indians nearly the entire way back.

In 1581, silver prospectors from northern Mexico again made their way into the Pueblo territories. They also found neither mineral riches nor golden cities. But they did find that the land of the Puebloans could support livestock and farming. That changed everything. Don Juan de Oñate made the journey north in 1598 with settlers, livestock and 10 Franciscans to occupy and claim the territory for the King of Spain. He almost immediately assigned a friar to Pecos who started things off very badly with his religious bigotry and idol-smashing. In 1621, the Franciscans sent Fray Andrés Juarez to Pecos as a healer and builder. His relationship with the people of Pecos was much better. Under his direction, the Puebloans built the most imposing mission church in all of Nuevo Mexico, with towers, buttresses and huge pine-log beams.

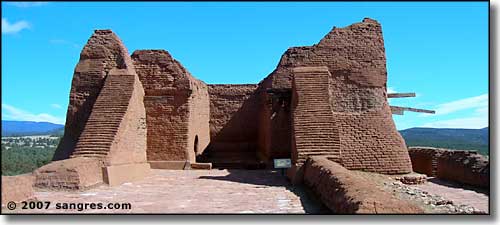

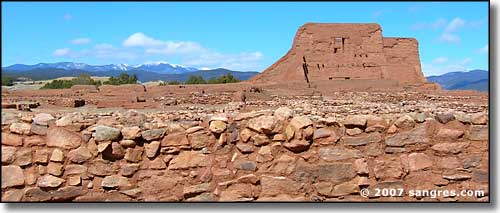

Another view of the mission

This was also about the same time that church and civic leaders began vying with each other for the Indians' labor, tribute and loyalties. What the Puebloans experienced of this was an ever-growing economic hardship and religious repression. The decades of Spanish demands and Indian resentments climaxed in the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. At Pecos, the local priest was warned but he didn't leave. He was soon killed by the tribe and the church was completely destroyed.

Don Diego de Vargas returned at the head of his army in 1692. He expected to have a fight on his hands at Pecos but found their opinion had shifted. The Indians welcomed him and actually supplied 140 warriors to help him retake Santa Fe. This time around, the Franciscans moderated their religious zeal and abolished all tribute. In return, the Pecos became partners in a relaxed Spanish-Pueblo community and rebuilt the mission church at Pecos, although the new church wasn't as imposing (or as costly in labor) as the previous one was. However, by the 1780's, disease, migration and Comanche raids had reduced the population at Pecos to less than 300. When Santa Fe Trail trade began flowing through the valley in 1821, Pecos was almost a ghost town. The last survivors left the empty mission church and decaying pueblo in 1838, moving to join Towa-speaking relatives at Jémez Pueblo, 80 miles to the west. Many travelers along this part of the Santa Fe Trail left the main route of the Trail to visit the ruins of Pecos and romanticize about the "ancients" who'd left this remarkable construction behind.

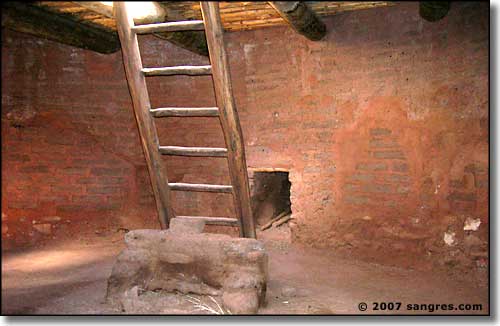

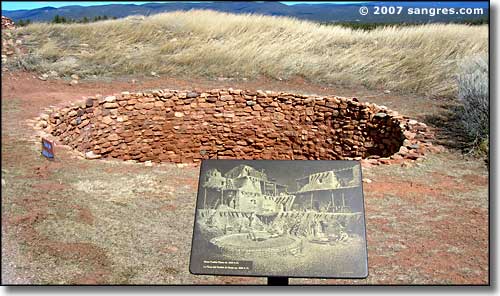

Inside one of the reconstructed kivas

A kiva inside the North Pueblo ruin with a drawing of what the North Pueblo may have looked like

The rebuilt Mission Church from inside the convento

The view from the Park headquarters, with the Sangre de Cristo's in the distance

The Governor of Jémez Pueblo still recognizes an honorary Governor of Pecos Pueblo among their descendants and members of the tribe make an annual pilgrimage back to Pecos for religious ceremonies.

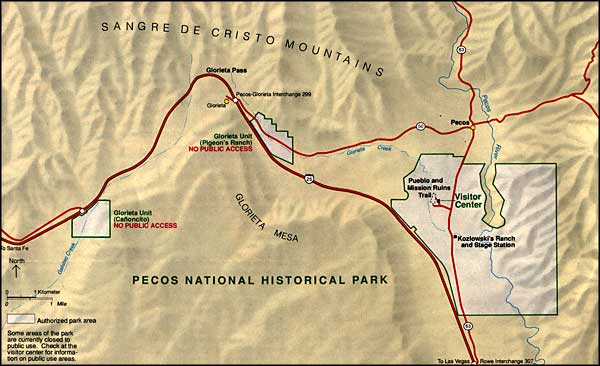

Map of the Park

From the time of the AV Kidder excavation at Pecos

In 1915, an archeologist named Alfred Vincent Kidder came to the ruins at Pecos to test his theory of stratigraphic dating using the pueblo's great trash mounds. In his words, "There is no known ruin in the Southwest which seems to have been lived in continuously for so long a period." He began excavating with the premise that the trash at the bottom of the pile was most likely the oldest, and from changes in pottery styles and other remains he should be able to at least determine relative dates and a general time-sequence that would be usable at many Southwestern sites.

The photo to the right is of the remains of an early tribal home at Pecos. The upturned stones define the edge of a stone-lined cooking area. The stone-lined trench in the middle kept drainage water contained as it passed through the building. To the left of where I took the photo are the remains of several of the early pithouses from Basketmaker days. Behind me was the convento: where the Pecos Indians were instructed in European trades and farming and animal husbandry techniques.

The great trash mound on the pueblo's east side (previously thought to be a natural part of the ridge) proved to be a major time capsule for Kidder. In 12 field seasons spent at Pecos, he found centuries of discards laid down in exact chronological order and, with no sophisticated dating technology, he was able to identify periods of occupation at Pecos through changes in the styles and manufacturing techniques of the pottery and shards he found. In 1927 he invited archeologists from all over the Southwest to the first Pecos Conference to develop the "Basketmaker and Pueblo" system of classification that is still used to identify cultural development among the Southwestern peoples.