|

The Pueblo Revolt of 1680 Part 2 |

|

|

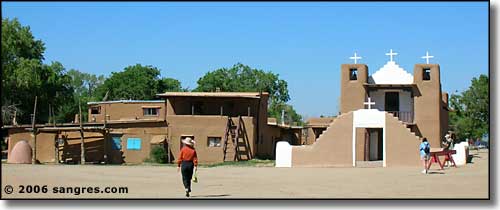

Taos Pueblo today |

|

The 1680 Revolt: Popé was a medecine man of San Juan Pueblo. He is widely credited as being the architect of the Pueblo Revolt. What he did was convince his people and the other Pueblos that the differences between them were really minimal. And if they didn't start to unite in the face of the Spanish threat, then the Spanish would eventually kill them all. It took years of work and much careful planning but they did achieve unity for a long enough period of time to evict the Spanish from northern New Mexico for several years.. One of the first things the Indians had to do was to remove all of their own potential traitors from the scene. This required the killing of Popé's son-in-law and several other tribal officials who derived their power from the Spaniards. Then they had to somehow enforce an absolute limit on who and how many knew about the plan. Even with all their precautions, rumors still circulated and the Spanish Secretary of War for all New Mexico warned Popé directly to stop his agitation or he would be punished. With this, Popé moved to Taos Pueblo. In Taos Pueblo, Popé was far more free to speak his mind, and his revolutionary work went much faster there. He gathered together with other medecine men and tribal leaders and slowly a plan took shape. One of the elements of the plan involved recruiting the Apaches to fight against the Spanish. Another element was planning the revolt for when the Spanish would be the weakest: just before the supply train of 1680. After observing the weather, checking the mountain snowpack and measuring waterflow in the Rio Grande, they picked a date in the second week of August as the most auspicious for their endeavor. Then someone had an idea: maybe they didn't get rid of all the traitors and they couldn't begin something like this without being able to trust all their people. So they sent runners out to all the villages with a message setting the date at August 13. The Spanish-appointed tuyo of San Cristobal betrayed them and the runners were caught, questioned and then killed. However, the Spanish thought they had 4 days to prepare for the revolt when the real date set by Popé and his compatriots was August 10, the very next day. The Spanish didn't have a chance. With 80+ years of ever-building rage behind them, the Indians made short work of most of their objectives on August 10, 1680. The attacks began at first daylight, all over northern New Mexico. After killing anyone of even half Spanish descent, the Indians took whatever they wanted from the homes and then burned the homes and the churches. Throughout the day and evening, frightened refugees arrived in Santa Fe with stories of savage murders happening everywhere around them. These folks were wanting to hide behind the walls and thick gates of the government compound. Among these folks were rebel spies, there to gather information and spread rumors. By nightfall, more than a thousand people had gathered behind the government walls. Among the stories being spread through the crowd were several in which all the Spaniards north of Santa Fe and south as far as Isleta were killed. The only Spaniards left alive in New Mexico were those in Santa Fe. It helped when the Lieutenant Governor's dispatch from Isleta was intercepted, leading the Governor in Santa Fe to truly believe that he was cut off from help by this rebellion of the Indians. At the same time, in Isleta the rumor was being spread that all the Spaniards in Santa Fe were dead and the Indian warriors were headed south to Isleta. Between these two stories, the Spaniards in Santa Fe and those in Isleta decided to not try to help each other. On August 13, a mass of warriors from the south arrived at the southern edge of Santa Fe. At their head was a man named Juan. Juan had formerly been the Governor's private servant. Juan rode into the capitol to negotiate with the Governor, General to General. The Governor was highly offended and furiously ordered Juan to take his rag-tag army and go home peacefully. Juan went back to his warriors and they waited. The next day, the mass of warriors from the north arrived. The day after, the attack on Santa Fe began with warriors pushing their way into town from two sides. About 2,500 warriors took part in this assault and, for most of it, the fighting was building to building. At one point, the only thing separating the Indians from the Spaniards were the massive oak doors on the chapel. The Indians set fire to the doors but never could burn through them. If the Indians could have gotten through those doors, every Spaniard left in the city would have been dead before nightfall. But the doors were too tough, the Indians decided to take another tack. With Spanish shovels and hoes, the Indians dug a new water ditch and diverted the artificial water flow that fed water into the government compound. |

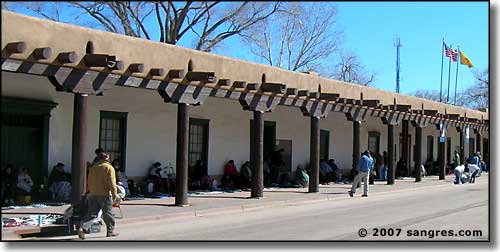

The Palace of the Governors, on the Santa Fe Plaza |

|

Two days later, the Governor himself led a surprise sortie out through the front gates of the Governor's Palace. The Indian rebels were caught completely by surprise and many of them were ridden down by the cavalry's horses as they tried to escape. Then the soldiers went into some of the nearby homes and set them on fire. The fire moved from building to building easily and, before it was over, probably 300 Indians died in the flames. This was the only major loss on the Indian side from the events of the revolution. As the fire was burning, the Spaniards were capturing people as they ran out of the burning buildings and they returned to the government compound with these prisoners and with several barrels of much needed water. The Governor questioned the prisoners and heard story after story of the killing of Spaniards everywhere. After hearing the testimony of 47 prisoners, he ordered them all taken out into the plaza and executed. That night the surrounding Indian warriors burned every structure that was still standing outside the government walls. Now the big question was about when the next supply train would arrive. The Spanish leaders agreed that the best thing for them to do was to go out and meet it. On Monday, August 21, 1680, the doors to the government compound opened and about 1,000 people (many were slaves, many more were servants) walked out. The wounded shared two ox-drawn wagons with the governor's records and personal valuables. There were about 400 dehydrated and starving horses and oxen in the crowd carrying people or goods. Everyone in this group expected to be massacred once the Indians outside saw how pitiful they were. Instead, the Indians waiting outside let them go. The revolutionaries were so happy to see these Spanish tyrants go that they allowed them to leave in peace. Bands of revolutionaries followed the Spanish southward to make sure they kept going but not one more Indian life was risked in the revolution. They had won, for the moment. |

|

|

|

| Index - Arizona - Colorado - Idaho - Montana - Nevada - New Mexico - Utah - Wyoming National Forests - National Parks - Scenic Byways - Ski & Snowboard Areas - BLM Sites Wilderness Areas - National Wildlife Refuges - National Trails - Rural Life Sponsor Sangres.com - About Sangres.com - Privacy Policy - Accessibility |

| Photos courtesy of Sangres.com, CCA ShareAlike 3.0 License. Text Copyright © by Sangres.com. All rights reserved. |