|

The Pueblo Revolt of 1680 Part 3 |

|

|

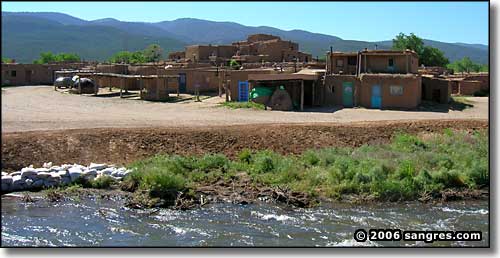

Taos Pueblo today |

|

After the Revolt: Men from every village had died in the uprising. After the Spaniards left, each Pueblo went about gathering up their dead and giving them proper burials. Their native religions were practiced in public for the first time in many years. They began to recognize themselves as people again. But once the Spanish were gone, the need for unity went with them. Each village returned to minding its own affairs and letting their neighbors do the same. Popé and the other medecine men were aware that the Spanish would be back but, over the years, they were unable to convince their people of that. In 1688, Popé died and his wisdom died with him. His people buried him with the fullest of honors but he wasn't there to help them when they next needed it most: 1692. 1692 marked the entry of Don Diego de Vargas on the scene. The King of Spain sent de Vargas to Chihuahua with a military commission to retake New Mexico and a letter of introduction to the Governor of Chihuahua asking for assistance. The Governor of Chihuahua informed de Vargas that the only possible soldiers he could spare for a venture into New Mexico were actually prisoners in the Governor's jails. De Vargas investigated as best he could and then took the Governor up on his offer. So the Conquistadors who helped the Spanish retake New Mexico were originally condemned prisoners, prisoners who were told they'd be shot on sight if they ever returned to Mexico. These prisoners had great incentive to be successful in their mission. Several miles outside the gates of Chihuahua, the Governor's dragoons turned over several wagonloads of weapons to de Vargas and company and then the Conquistadors marched northwards into history. The retaking of New Mexico wasn't very bloody. All of the Pueblos had fallen out with each other and the centuries-old jealousies and bickering had taken over their societies again. As primarily agrarian societies, they didn't really have a warrior class: they couldn't defend themselves. On top of that, individuals from certain Pueblos worked with the Spanish to help them retake other Pueblos by sharing their knowledge of back doors, defensive strategies, etc. When the Spanish settled back into northern New Mexico, they did things differently. Even the missionaries. Many Indians came back to practice Mass but at the same time they were openly involved in kiva ceremonies and public sacred dances. The Spanish never again tried to make village Indians change their ways. They also made a new rule: no one who was not of Spanish blood was allowed to bear Spanish arms nor were they allowed to own or ride horses or mules. And slaves had to come from outside Spanish ruled territories, from tribes that were clearly not under the King of Spain's domain. In the end, it looks as though the Pueblo Indians and the invading Spaniards reached a compromise that was much more respectful of the Indians. This compromise held until 1821 and the Mexican Revolution. The Mexicans won and when the Spanish left, they took all the priests. The Mexican territories were thrown into an uproar with the collapse of Spanish feudalism and its religious sub-trappings. Northern New Mexico and southern Colorado saw the rise of Los Hermanos Penitentes to fill the religious void created by the on-going expulsion of Spanish citizens (and priests), and to carry on with the civic duties the people needed fulfilled. Then the next big shock the Pueblo Indians faced came with the Mexican-American War in 1846-1848, but that's another story. |

|

The only materials we now have that record the events being recounted here are Spanish in origin and are highly suspect (in my book anyway). The Spanish had a great investment in making themselves look perfectly good and blameless for what happened before and during the Pueblo Revolt, and in painting the most horrible, savage and blame-filled picture they could of the Native Americans. In 1973, Franklin Folsom published Red Power on the Rio Grande: The Native American Revolution of 1680. In this book, he examines the Spanish records from the Pueblo Indian perspective and arrives at what is probably the most close-to-true narrative of what really happened back in those days. I highly recommend it to anyone who is truly interested in learning a bit about the "other" side. |

|

|

|

| Index - Arizona - Colorado - Idaho - Montana - Nevada - New Mexico - Utah - Wyoming National Forests - National Parks - Scenic Byways - Ski & Snowboard Areas - BLM Sites Wilderness Areas - National Wildlife Refuges - National Trails - Rural Life Sponsor Sangres.com - About Sangres.com - Privacy Policy - Accessibility |

| Photos courtesy of Sangres.com, CCA ShareAlike 3.0 License. Text Copyright © by Sangres.com. All rights reserved. |