|

|---|

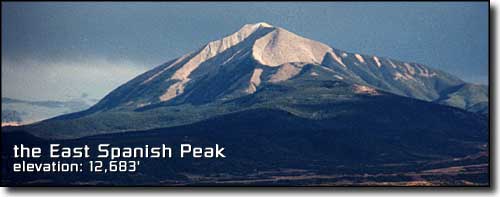

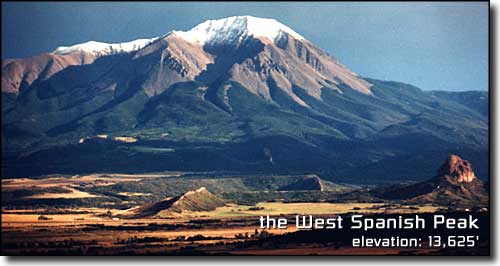

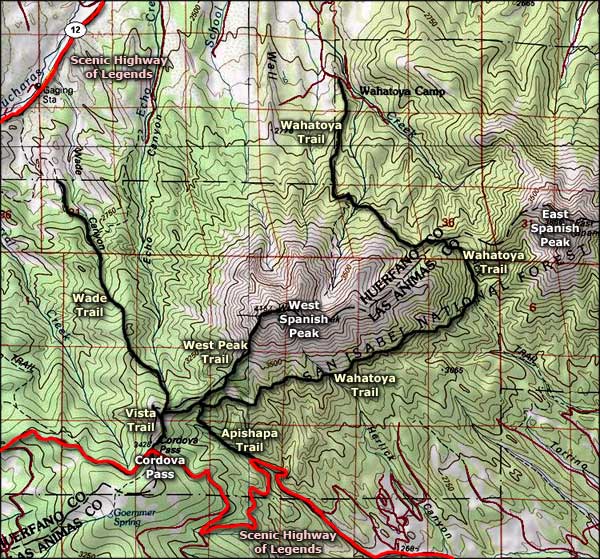

The Spanish PeaksLas Animas & Huerfano Counties, Colorado |

|

|

|

|

The Basis of the Legends

The Spanish Peaks of south central Colorado have been among the most important landmarks of the southwestern United States, guiding Native American tribes, Spanish and French trappers, gold seekers, hunters, and American settlers. The Ute, Comanche, Apache, and other, earlier Indian tribes held the Peaks in religious awe and named the mountains Wahatoya, meaning "Breasts of the Earth." Even the ancient Aztecs believed the Peaks were a source of hidden treasure. Later travellers named them the Twin Peaks, Dos Hermanos (Two Brothers) and Mexican Mountains. Whatever their name, the Spanish Peaks are a truly unique and majestic contribution to the area's already beautiful scenery. Travelers from the east see these peaks from as far as 100 miles distant. There are miles and miles of aspen, Ponderosa and bristlecone pine, blue and Engelmann spruce, several different firs, and many, many varieties of alpine flowers. In the fall, hillsides of multi-colored oak are contrasted with the brilliant yellow of the many aspen groves. Legend has it the first Europeans to enter the Spanish Peaks area were Spanish militia in the company of a group of priests, sent to look for gold wherever they could find it. Supposedly they found a rich vein somewhere on the Peaks and enslaved some local Indians to dig it out for them. When the Spaniards left they killed all the Indians and headed south over Cuchara Pass. They went down to the Purgatoire River and headed west, hoping to cross the Sangre de Cristo's. Somewhere along the banks of the river they were ambushed by hostile Indians and were wiped out to a man. That's how the river got its' name: Rio de las Animas Perdido en Purgatorio (River of Souls Lost in Purgatory, changed to Purgatoire by French trappers and Picketwire by a later wave of English speaking settlers). |

|

|

The first recorded Europeans to explore the Spanish Peaks region came north from Santa Fe in 1706 (Juan de Ulibarri), 100 years before Zebulon Pike discovered Pikes Peak. There were several forays into the area by northern New Mexico militias looking to put an end to the continual raids from the Comanches. De Anza finally succeeded in this mission when his men killed Cuerno Verde (Green Horn), a great Comanche war chief, somewhere in the Apache-Colorado City area at the foot of Greenhorn Mountain. Pike was sent to explore the new territory in 1806. He followed in the footsteps of the old French trappers and traders. The Santa Fe Trail was established in 1821 with the Spanish Peaks as guideposts to travelers along the Mountain and Taos Branches of the Trail. From Bent's Old Fort the Mountain Branch went southwest past the Peaks through Trinidad and over Raton Pass and on to Cimarron, Wagon Mound, Las Vegas, and Santa Fe, New Mexico. The Taos Trail passed north of the Peaks along the Huerfano River, up Oak Creek and over Sangre de Cristo Pass to the San Luis Valley and then south to Taos, New Mexico. Explorers, lawmen, gunslingers, and mountain men with names like Kit Carson, Black Jack Ketchum, Wild Bill Hickock, John C. Fremont, Uncle Dick Wootton, Zane Grey, William Bent, and Bat Masterson travelled the area frequently. The peaks were once the scene of extensive mining activity. Around 1876 a minor boom in mining gold from these mountains occurred, with as many as 60 new shafts opened. Another burst of activity happened around 1900. The mines were then worked sporadically until the 1940's and then abandoned. Many open shafts remain, and extreme care should be taken around them. There are several trails to follow to reach the summits of each of these mountains. Inquire with the US Forest Service. And always be aware of the weather. Never try to climb either of these mountains with snow on them. The summer lightning hazard is also very high. |

The Geology of the Spanish Peaks |

|

Sedimentary Rock

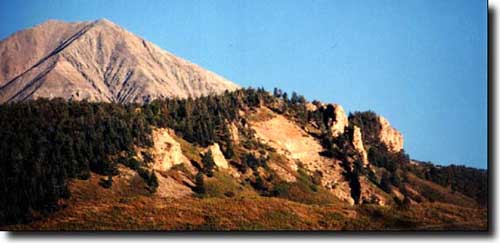

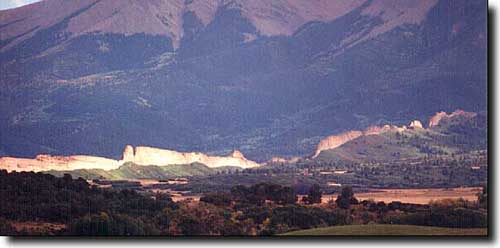

Millions of years ago the area that is now the Rocky Mountains and Great Plains was at the bottom of an inland sea. Thousands of feet of sand, silt, mud, clay, and marine fossils were deposited here over the years. When the mountain building process began and the area began to rise, these deposits emerged from the water as Sedimentary Rock. To the geologists, the Spanish Peaks are prime examples of "stocks." A stock is defined as a large mass of igneous (molten) rock with intruded layers of sedimentary rock that was later exposed by erosion. When mapped by geologists, the Peaks were found to be masses of granite, granodiorite and syenodiorite. The East Peak is a nearly circular intrusion about 5 1/2 miles long by 3 miles wide while the West Peak is a mass about 2 3/4 miles long by 1 3/4 miles wide. Among the most unusual features of the Spanish Peaks are the great dikes which radiate out from the mountains like spokes of a wheel. These walls of rock are often spectacular in height and length and are known to geologists world wide. The dikes are made of intrusive igneous rocks which forced their way into seams in the sedimentary rock. Erosion wore away the softer sedimentary leaving walls of hard rock from 1 foot to 100 feet wide, up to 100 feet high and as long as 14 miles. At least 400 separate dikes have been identified by geologists. This scenic combination of two great stocks and hundreds of impressive dikes is unique. Nowhere else are these geologic phenomena found in these patterns, in such variety of rock type, or in as great length, height, abundance or beauty. The formation of the Spanish Peaks and dikes began many millions of years ago. For eons inland seas washed the area of the Great Plains and the Rocky Mountains and thousands of feet of sand, mud, silt, clay and marine animals were deposited. As time went on these deposits emerged from the water as layers of sedimentary rock. For a period from 35 to 75 million years ago the sediments in the area were subjected to stresses which caused cracks and seams to form. A trough along the eastern side of what is now the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, the most southerly range of the Rocky Mountain System, was formed by pressures on the earth's crust from the west. About 35 million years ago the pressures to the west increased, the sediments cracked and at the same time molten rock began to surge upward into the layered rock. Great fluid masses of molten rock invaded the soil sedimentary rock by melting the sediments and assimilating them into the hot magma. Meanwhile the thick molten rocks entered the cracks made by the earlier folding of the trough to the west. The molten rock squeezed its way into the cracks like mud between a boy's toes. In the 25 million years since the upheaval, the rains, frost and winds have worn away the softer overlying sediments exposing the harder igneous rock of the Spanish Peaks and their dikes. |

|

Batholiths and Stocks

27 million years ago, pressures and stresses built up by continental drift movements caused cracks to form in the sedimentary formations. The Sangre de Cristo Mountains were pushed up in one huge chunk between two major faults running north to south. Molten rock from the mantle beneath the Earth's crust began to surge upward into the lower areas of the cracked formations about 25 million years ago. When the magma cooled and hardened beneath the Earth's surface it formed large horizontal "Batholiths" of granite called "Stocks", which is what forms the Spanish Peaks. Several miles of sedimentary rock covered the Spanish Peaks stocks. Over the last 25 million years, uplifts and folds have raised the surface of the land. The elements have eroded away the softer overlying sedimentary rocks and exposed the underlying hard, igneous stocks of the Spanish Peaks. While the surrounding area is marked by many lava flows and volcanic mountains (some of which have been active as recently as 10,000 years ago), the Spanish Peaks are not extinct volcanoes. About 20 miles to the north-northwest are Mt. Mestas, Silver Mountain, Sheep and Little Sheep Mountains, and Iron Mountain. All of these mountains are also stocks. |

The Great Dikes |

|

When the molten magma was rising in the Earth it was also moving through vertical cracks and joints, spreading out in all directions like the spokes of a wheel. As erosion occurred these dikes were exposed. They vary from 1 to 100 feet wide and up to 14 miles long. The dikes are a prominent feature of the landscape around the Spanish Peaks. There are two systems of radial dikes and a separate, older system of semi-parallel dikes tending N80E in the area. One of the systems of radial dikes is centered on the West Spanish Peak. The other is centered on Silver Mountain. An area east of Silver Mountain, known as the Black Hills, is composed of the same materials as the dikes. |

The Long Wall  Spanish Peaks area map |

|

|

Spanish Peaks Related Pages

Climb West Spanish Peak - Spanish Peaks Gallery

Scenic Highway of Legends - Las Animas County - Huerfano County -- West Peak Trail San Isabel National Forest PagesColorado Pages

Towns & Places - Scenic Byways - State Parks - BLM Sites - History & Heritage Ski & Snowboard Areas - Photo Galleries - Colorado Mountains - Scenic Railroads Unique Natural Features - Wilderness Areas - Outdoor Sports & Recreation Colorado's National Forests - National Wildlife Refuges - Colorado's National Parks |

|

| Index - Arizona - Colorado - Idaho - Montana - Nevada - New Mexico - Utah - Wyoming National Forests - National Parks - Scenic Byways - Ski & Snowboard Areas - BLM Sites Wilderness Areas - National Wildlife Refuges - National Trails - Rural Life Advertise With Us - About This Site - Privacy Policy |

| Photos courtesy of Sangres.com, CCA ShareAlike 3.0 License. Map courtesy of National Geographic Topo! Text Copyright © by Sangres.com. All rights reserved. |