The Scenic Highway of Legends

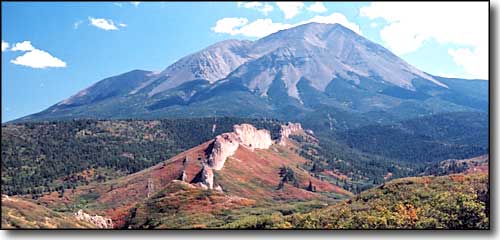

Cuchara Pass to La Veta

Looking north over Cuchara from the Farley Overlook

that's the Dakota Wall across the middle of the photo

Cuchara River

The road descends quickly from the summit of Cuchara Pass, through the aspen groves to a hairpin turn across the Cuchara River where it flows out of the mountains. At that hairpin turn is the road going west to Bear Lake, Blue Lake and Trinchera Peak. Between here and Blue Lake is 4 miles of excellent stream fishing.

Asa Arnold was the first Forest Ranger for the newly formed San Isabel National Forest in 1907, serving in that capacity for three years. Arnold built many of the National Forest trails in the area, including the Apishapa Trail, Blue Lakes Trail, Indian Creek Trail and the Chaparral Trail.

Shortly after he became Forest Ranger, it was found that a bear had been killing range cattle in the Blue Lake area. Arnold trapped the bear near a lake north of Blue Lake. The bear, being extremely large, dragged the trap and the log to which it was attached into the lake. Asa used his saddle horse and pack horse to pull the bear, the trap and the log out of the water. From that time on the lake was known as Bear Lake.

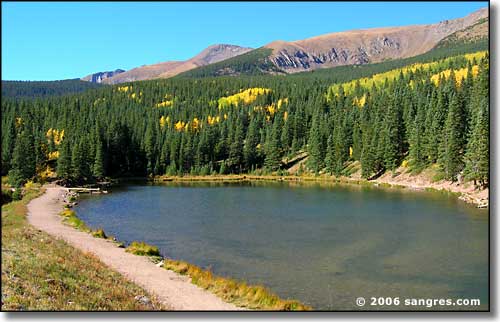

Bear Lake

Blue Lake

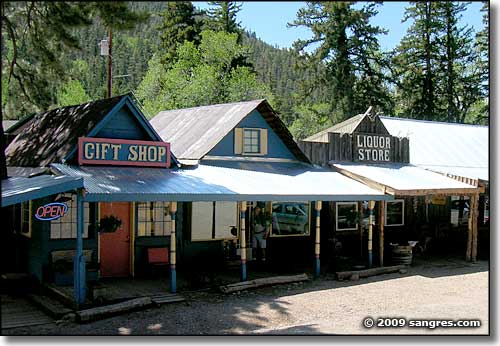

In Downtown Cuchara

The paved road continues on to the town of Cuchara. Downtown Cuchara is a wonderful rendition of a turn of the century Colorado mountain town, complete with slabwood siding and some full log construction.

The earliest records of the Cuchara Valley show that it was not called Cuchara at all, but rather Nunda Canyon (Nunda is a Native word for potato). Sometime in the late 1800's it was first referred to as Cuchara Valley. The first Anglo settlers were homesteaders of the "rush" days. Land was free for the taking as long as the homesteader built a house with a door and at least one window on the property.

Those first settlers found the climate and soil in the high meadows between Stonewall and Cuchara well suited for growing potatoes, a crop that was also raised by the Native Americans. The farmers spent their summers growing potatos to sell in Trinidad in the fall, and then spent their winters making cheese from their goats' milk to sell in town in the spring. But they failed to rotate their crops and soon the soil was depleted of the nutrients necessary to grow potatoes and most of these farmers moved on.

In 1908, George Mayes and his wife moved to the Valley for Mayes' health. Seeing the beauty here, Mayes was convinced the area would make a great summer resort. He named his resort Cuchara Camps and by 1910, several summer cabins had been built and Cuchara was a community, at least in the summer.

Cuchara is Spanish for "spoon." Some say the river and valley received their names because early explorers found ancient spoons along the River. Others say the name was given because of the spoon shape of the Valley. They claim that when giants roamed the Earth, the Valley was formed when a giant laid down his spoon after a heavy rain, thus making an impression in the side of the mountain. The impression has remained.

The West Spanish Peak from the Gap in the Dakota Wall

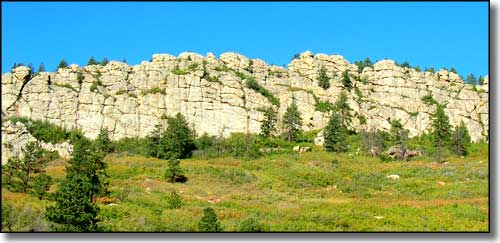

This is the same Dakota Sandstone Wall that you passed through in Stonewall. This same "break" in the North American continent stretches from Canada to Mexico along the fault line that marks the eastern edge of the upthrust that created the Ancestral Rocky Mountains during the Laramide Orogeny, some 65 million years ago. This sandstone was originally deposited on an ocean bottom and compressed over time by the weight of layers of rock, gravel and stone deposited above it. While this exceptionally hard layer of sandstone was tilted upright when the ancestral mountains were first pushed up, those softer mountains have mostly eroded away and left only these vertical walls behind in testament to their passing. While the rock of the Sangre de Cristo's is older than the Dakota Sandstone, the Sangres were pushed up only about 27 million years ago, roughly along the same fault lines as the Ancestral Rockies in this area. This particular gap in the Wall was created over the years by the Cuchara River.

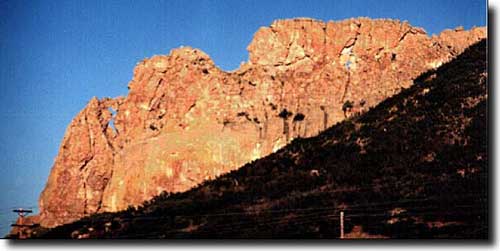

The Dakota Wall, just north of the Gap

All the rock formations here are granite dikes radiating from the West Spanish Peak

the farthest one is the Devil's Stairstep, still to the north

"Many years ago," says a Native American legend recorded in the Mexico City archives, "before the first white man stepped ashore, even before the alliance of the three kingdoms, Alcolhua, Aztec and Tepance, gold was already an eagerly sought article. But it was not coined in those days, nor was it used as barter; it was offered to the deities only, and with it the shrines of Huitzilopochtli were decked. But when Nezhuatcoyotl reigned in splendor at Tezcuco, the gods of the Mountains Huajatolla became envious of the magnificence of his court and they placed demons on the double mountain and forbade all men further approach."

When Coronado returned to Mexico after his search for Quivira, he left behind three monks and others of the group to begin a colony. Two of the monks tried to bring Christianity to the Native Americans, both died for their efforts. The third monk, Juan de la Cruz, found the rich gold and silver mine of the legends. He claimed to have overcome the demons of the mountains. Native Americans of the Pecos region reported that their people were forced to work in the mine, bringing out gold and silver ore. When the slaves had served their purpose, they were all killed. Juan de la Cruz and his followers loaded a number of pack animals with the ore and left for Mexico. They were never seen again. Gold nuggets that might have been part of their treasure were found later, scattered along an ancient trail.

The West Spanish Peak rising above the Devil's Stairstep

The Devil's Stairstep is one of the grandest dikes in the area. Over 400 dikes radiate out from the West Spanish Peak like spokes on a wheel, and continue either above or below ground for as far as 25 miles. There is another set of similar dikes radiating outwards from Silver Mountain, across the valley to the north. These geological formations are unique to this area.

Eons ago, when the Earth was new, the Devil was allowed out of his fiery home to survey the World. He chose the Cuchara Valey as his entrance, climbing up the Stairstep and sitting on the twin mountains. Surveying the World, he began plotting how to make it his. However, God knew of his plotting and, noticing the beauty of the Valley and surrounding mountains, God took it as His own and forbade the Devil to ever enter the area again. But the Devil's Stairsteps still stand.

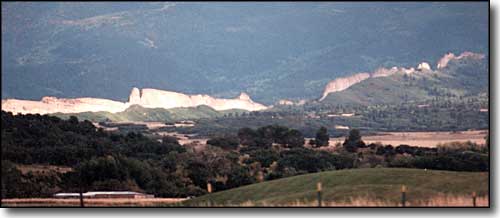

Looking south, just north of the Devil's Stairstep

Profile Rock

For those with a sharp eye, the profiles of George Washington and Thomas Jefferson (or some say Martha Washington or a Native American) can be seen in Profile Rock. There is also a train on a trestle and a rearing horse (or deer).

The Long Wall, of which Profile Rock is only a small part

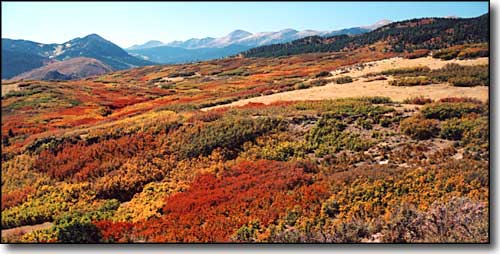

Looking up the Valley toward Cuchara

Goemmer Butte, near La Veta

a volcanic plug between Mt. Mestas and the West Spanish Peak,

Mt. Mestas to the left, Silver Mountain in center, Greenhorn Mountain to the right

The Native Americans tell of giants who once roamed the area around Wahatoya. A quarrelsome tribe, they built rock walls as breastworks for their wars, using huge boulders as weapons. The whole World reverberated from the sounds of their battles. The gods of Wahatoya watched as the tribe fought one another. They grew angry and withheld rain from the area. When water became scarce, the giants ended their fighting and went in search of water. They left behind one lone warrior to stand guard over their prized valley.

The giants never returned. The guard continued at his post. One day he sat down to rest and the gods, seeing his dedication, turned him into stone as a monument for all to see (Goemmer Butte).

It is said that Colonel John M. Francisco looked down upon the future site of La Veta and declared, "This is paradise enough for me." In 1862, shortly after his first viewing of the Valley, Francisco and his partner, Henry Daigre, began construction of a fort for commerce and protection purposes.

Chief Ka-ni-ache

In the spring of 1863, it is told, the Fort was placed under siege by Ka-ni-ache, chief of the Mouache Utes. The Utes approach was detected in time to bring all hands inside the Fort, including Col. Francisco. The Utes took up positions around the Fort, thinking the white men would eventually have to come out for water. What they didn't know was that the Fort had a well inside. But the Utes caused enough alarm that it was decided to send for help. Fort Garland was nearby but was also unmanned, so someone had to ride to Fort Lyon, 120 miles to the east.

Hiram Vasquez, who had been captured and raised by the Utes as a boy, volunteered to make the ride. That night he went over the west wall, holding onto a gun and a bridle. Outside the Fort, he found his mule and began riding easterly. He arrived at Fort Lyon less than 24 hours later. The next morning, Vasquez and the cavalry headed back to La Veta. By the time they arrived, Ka-ni-ache and his band had left, taking with them several head of the Fort's cattle. It seems that Francisco had talked with Ka-ni-ache and convinced him that not only could the Fort withstand any attack because they were well provisioned, but that the cavalry was also on its' way.

By 1871, there were enough settlers in the Valley to warrant a Post Office, so they called it Spanish Peaks. With the coming of the railroad in 1876, there was much land speculation and one group formed the La Veta Town Company. How "La Veta" (meaning "the vein" in Spanish) was chosen is anybody's guess but the name of town was changed and the La Veta Post Office was opened in 1876. As part of this speculation, the railroad station was constructed a couple of blocks north of the Fort and the center of business in town slowly spread in that direction.

Just northeast of La Veta the highway merges with US 160 and takes you into Walsenburg. Or, in downtown La Veta you can go west on Ryus Ave. and follow the pavement about 4 miles to US 160 and head on up past Mt. Mestas and into La Veta Pass on the way to Fort Garland, the Great Sand Dunes and the San Luis Valley.

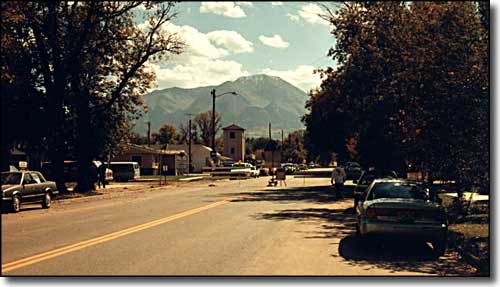

Looking south in La Veta